Chapter 0 - Introduction: Student Questions!

This page has public answers to some of our most frequently asked questions for this chapter.

Question not answered here, but you’d like it to be? Shoot us a voice message and we might feature it here and in the podcast!

Terminal/command line syntax: How to get the terminal to listen to your commands

The terminal can be confusing when you first start using it. After a while it will become second nature.

The terminal only accepts sentences in a certain format and gets really confused if you give it something else.

Anatomy of a terminal command

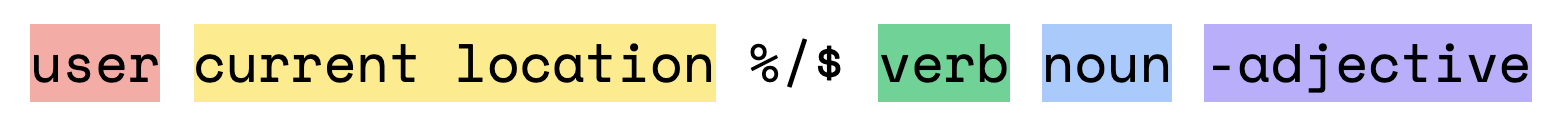

Any given line in a terminal window will look like this:

- The username of whoever is using the terminal. (Probably your name.)

- The current folder on your computer where the terminal window is operating out of. This is important context because when you’re opening files, you’ll have to give the terminal directions on where to find those files from where you are currently.

- A symbol separating that contextual information from the stuff you’ll type in. Sometimes this is a %, sometimes it’s a $, sometimes it’s a > or something else. You can’t type to directly modify the symbol or anything before it, but you can change your user and location through commands.

- The command you are executing.

- The thing you want to execute that command on or with.

- Optionally, you’ll also see “flags” at the end of a command denoted with a

-. These are kind of like adjectives that modify the command you’re giving.

(Some terminals will have 1 and 2 in a different order, but everything you put after the symbol (3) is the same order every time no matter what.)

Importantly, all of these elements are always separated by spaces.

Some examples of this:

Change the folder you’re in

username currentFolder % cd newFolder

The verb is cd (“change directory”) and the noun (place) we want to cd to here is newFolder.

After you run this command, newFolder should replace currentFolder on the left.

You can also give it a whole path to a different folder, e.g. cd insideFolder/path/to/anotherFolder/newFolder2. In this case, newFolder2 will replace currentFolder once the command is executed successfully.

Run a Python program

username currentFolder % python pythonFile.py

The verb is python and the noun (program) we want to python here is pythonFile.py. If your python program is in a different location than currentFolder, you’ll have to tell the terminal where to find it, e.g. python insideFolder/pythonFile.py.

See who owns a particular Web address (Mac/Linux only)

username currentFolder % whois ncf.edu

For this command, the current location doesn’t matter at all. The verb is whois and the noun (website) we want to whois here is ncf.edu. When you run this command, the whois program built into your (Mac/Linux) computer will search internet directories to find out who owns the domain name you specified.

If you want to learn more about the command-line interface and things you can do with the terminal, I found this cool guide with a lot of good information for beginner to intermediate terminal users.

Example with flags: Prevent your computer screen from turning off (Mac only)

Warning: This command might be dangerous

username ~ % caffeinate -d

In this example, the verb is caffeinate and the -d adjective describes how to caffeinate. The d stands for display. You could replace the -d with another flag to make something else happen, e.g. -i to prevent idle sleeping.

The flags (adjectives) available for any particular command (verb) depend on the command itself. You will probably not need to use flags for this course, but it’s good to have seen them before in case you ever need to use them for something else.

Common mistakes

Mistake 1: Misunderstanding the difference between nouns and verbs

I have seen some people say cd python3 hello.py. This confuses the terminal because it sees cd python3, thinks “okay, we’re changing directories to python3,” then one of two things happen:

- There isn’t a

python3folder inside the current folder, so the terminal says “I can’t move topython3because it doesn’t exist.” and dies. - There is a

python3folder inside the current folder, so the terminal moves there. It then sees a second noun—hello.py—and doesn’t know what to do with it becausecdcan only change directories to a single place.

Remember that the terminal can only handle one verb at a time and the verb you use affects what kind of noun it’s expecting to see next.

Mistake 2: Accidentally swapping the spaces with another character

I have occasionally forgotten to put a space after a cd command, which confuses my terminal. For example, if I say:

eleanor@embp ~ % cd/Users/eleanor/Documents/thesis/lists

the terminal thinks the verb I’m giving it is cd/Users/eleanor/Documents/thesis/lists and it’s like, “what? I don’t know how to do a cd/Users/eleanor/Documents/thesis/lists!” and dies.

Mistake 3: Typos

The terminal gets confused if the command you’re giving it is even one character off (see above.) If you’re getting a strange error, it’s possible that you spelled things wrong. Note that commands are also case-sensitive. (PYTHON ≠ python.)

Common error: “No such file or directory”

No such file or directory means that the terminal couldn’t find the thing you want to use/work on. This is most commonly due to a typo in your noun. Check to see whether you are in the right folder and make sure you spelled everything correctly.

Writing code and using the terminal is intimidating! Isn’t there a less scary way where I can just click buttons?

There are ways you can run Python by clicking buttons, but they are actually more complicated than typing in your terminal. The act of clicking a button does many more things inside the computer than just telling it python my_program.py which means there are many more moving pieces that can break. The buttons often don’t work the way you expect and it’s very difficult to isolate the problem. With the terminal, you can read exactly what’s happening at any given moment.

Who made the first programming language?

The first modern programming language is widely considered to be COBOL, based on work conducted in the 1950s by Grace Hopper. COBOL is actually still in use today!

How are programming languages developed? For what purposes are they created?

Programming languages are developed for all kinds of reasons by all kinds of people. Anyone who wants to can create a programming language. The process involves a series of decisions regarding what you want your language to do and how it should handle various use cases.

There are also people whose entire field of study revolves around programming languages. Heather Miller is one such person. PL researchers drive much of the world’s knowledge of programming language theory and they are often the first to come up with new and experimental methods of designing programming languages.

Most languages are also developed by communities of open-source contributors around the globe. Some of these contributors are volunteers and others are professional software engineers for whom building/maintaining a language is part of their job.

What makes Python special?

We like Python because it’s easier to read and write than some other languages and because most to all of the instructions we’ll write in this class are marginally simpler in Python than most other languages. That’s all—there are other reasons why Python is good, but it’s not the best language by any means (nor is there really such a thing as a “best” language, only languages that are suited for particular tasks.) Ellie’s other pick for a beginner-friendly language is Swift.

Python is popular for writing “quick and dirty” scripts to wrangle text. It’s also very widely used in data science and statistics. A large proportion of the Internet’s backend is additionally built in Python.

There are other languages that are better at other things. For example, Swift (aforementioned) was originally built for creating iOS apps.

A little more on programming language history & development

One student asked:

Do new programming languages derive from prior ones? Do older programming languages still have significant practical use now in comparison to those that were created more recently?

Answer: Yes & yes (though it depends on each specific language, of course.)

Python, Swift, Java, R, and hundreds of other languages derive from the C programming language invented in 1972.

C continues to be very useful today because of its strengths in embedded systems and small computers without a lot of resources. It has some fancier descendants that are easier to use while still keeping C’s strengths (notably C++ and Rust), but C itself is still widely useful across contexts and it still has an active team of maintainers.