Byte 1-3: Practicing Python Basics

“Hello World” is fun, but it’s more fun to build programs that do more things. You should listen to the episode and then download the practice worksheet.

(You might have to click “Save Link As…” to download the file.)

Once your file is downloaded, you can open and run it using the same method we used to create hello.py in Byte 0-2.

Addendum: It’s all in your head

A lot of you have been confused (and slightly intimidated) about what to do with this file once you’ve downloaded it.

In 0-2, we followed these steps to make and run our hello.py program:

- Open a plain text editor and write some Python code in it

- Save it as a

.py - Open a terminal window and tell it where the Python code file is

- Then tell the terminal to run the Python code

These are the steps you’ll follow every time you want to run any Python program.

This might be intimidating because it involves a lot of typing code into your computer like a hacker. It’s totally normal to feel like this is extremely technical—that’s because it is! It is a lot of text, especially if you’re used to buttons. I promise that once you get started working with this text, you’ll find that it actually isn’t any harder than using buttons. (It’s also much easier in the long run.)

The concept of a terminal dates back to the early days of computing. In the past, computers were large, unwieldy machines that filled an entire room. There was often only one computer per school or organization that everyone would have to share. Users interacted with these computers via a small connected screen called a terminal.

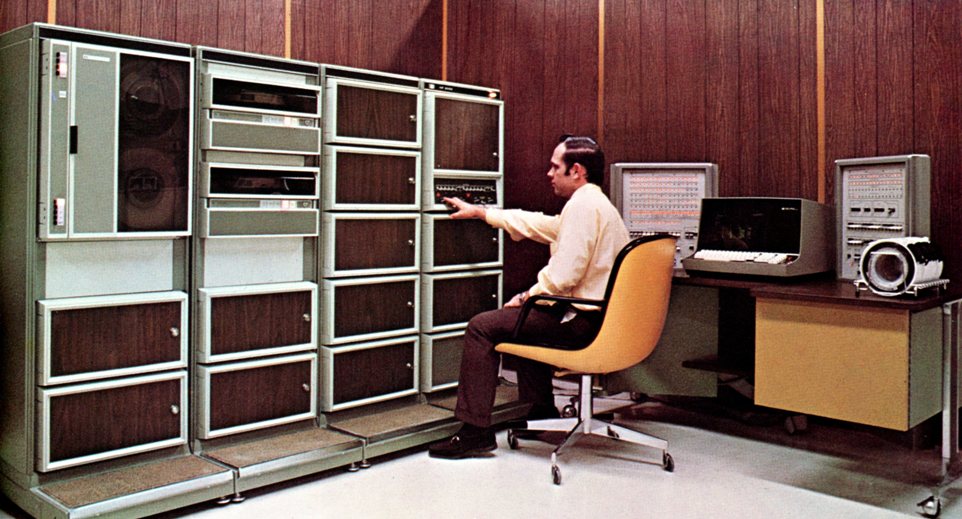

In the above photo, a person is flipping a switch on a mainframe computer. On the right you can see the terminal.

The actual code for these computers lived on punch cards or large magnetic tapes. (In this picture you can kind of see the tapes on the upper left.) You would use the terminal to tell the computer which set of cards or magnetic tapes to run.

Today our computers are much smaller and we store our code in files instead of physical magnetic tapes, but the process is the same.

To write and run Python, you first create a file with some instructions for your computer, then go to the terminal and tell your computer which file it should execute.

If you want to change your code, you can update your instructions in the file, save it, then tell the terminal to run it again… sort of like how you might physically remove a stack of cards from a mainframe, punch some more holes in it, put it back, and have the terminal tell the computer to try again.